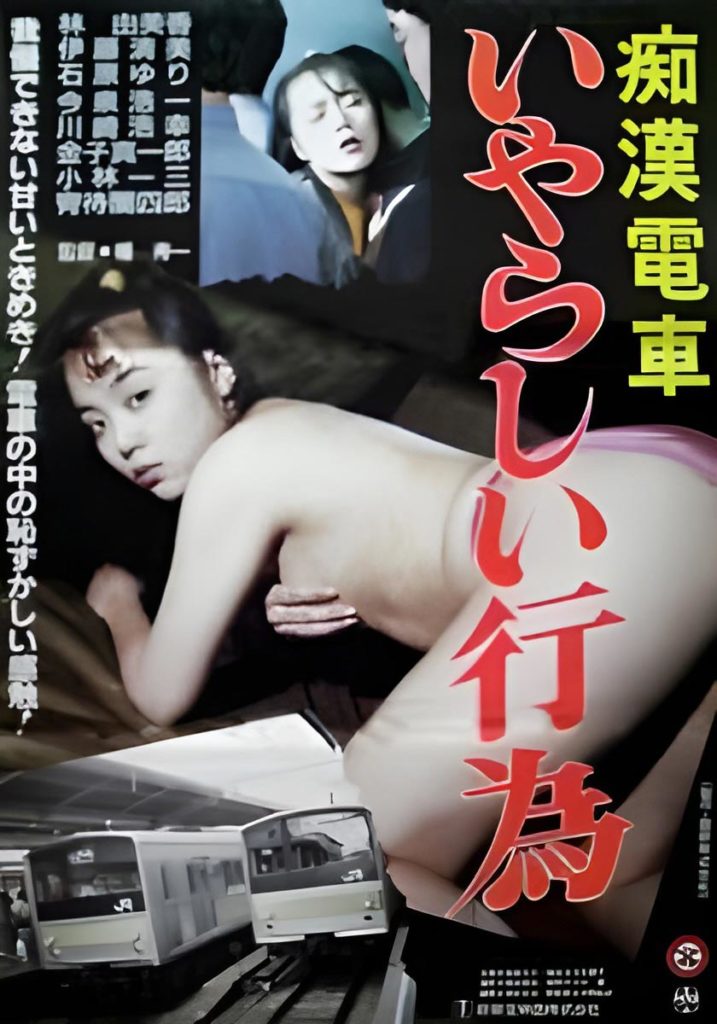

Molester’s Train: Nasty Behavior Movie Review!

Molester’s Train is a Japanese pinku series that has nearly 20 entries, yet is rarely, if ever, spoken about outside of Japan. Starting in 1982 with acclaimed director Yōjirō Takita’s Molester’s Train: Please Continue, the series enjoyed success during the early to mid-80s in Japan, with Takita directing nearly every film in the series during this time. Inspired heavily by early American “nudie-cuties” and works such as Russ Meyer’s Eve and the Handyman or HG Lewis’ Adventures of Lucky Pierre, the series retained a light and comical tone for nearly its entire run. Initially ending in 1989 with Get on Back, the Molester’s Train seemed to be over. That is until 1993, when the production company behind the Molester’s Train series, Shintoho Pictures, decided to resurrect the series. However, the studio decided to hire prolific pinku director Hisayasu Satô to direct the entry titled Molester’s Train: Nasty Behavior. Not only did this change the tone of the series, but it also helped to breathe new life into a series that had grown stale and was a moderate success in Japan. But enough background, what is the film actually about and what about the quality?

Nasty Behavior is a film that has a simple premise, focusing primarily on two characters. The first of which is a young man who films women on the train as they are molested and has a very complicated family. The second of which is a young woman who has recently lost her boyfriend and decides that she will commit suicide via blowing herself up with dynamite on her 20th birthday. The two meet and become romantically involved, with the film following their relationship. For fans of Satô’s other works (Splatter: Naked Blood), the tone of Nasty Behavior will come as quite a surprise. Rather than showcase extreme acts of violence and sexual depravity, the film takes a very restrained approach that is even less offensive than many other pinku films that were releasing at the time. This isn’t to say that the film doesn’t have its moments of perversion, but these moments are sadder and more depressing rather than titillating. This is a story of broken characters who have lost their connections with the rest of society, and their actions reflect this.

While the film’s violence and sexual content is far more restrained than his other works, Satô’s trademark existentialism and nihilistic worldview are on full display here. Gone is the light-hearted tone of the previous Molester’s Train entries, as they are replaced by a melancholic story of two teenagers who have lost all hope in themselves and the world as a whole. The concept of depersonalization is explored through our lead male character, who feels he is living in a world separate from everyone else. Rather than live his life, he films the lives of others and uses this to come up with his own worldview. He doesn’t quite understand others, and he doesn’t fit in with the rest of society. The female lead of the film is someone just as sad and hopeless, but for a complete opposite reason. Rather than being disconnected from society, she seems to be overly connected and in touch with society and can no longer take its pressure. When the two meet they seem to connect like puzzle pieces, and their self-destructive tendencies leads to a scene in a tent that is one of the most haunting ever put on film. Haunting is a word that describes the film, as the world portrayed in the film is at once bustling and emptily soulless. Satô is a filmmaker known for his ability to conjure a melancholic mixture of loneliness and crushing depression in his films. This film provides this in the most balanced way that the director ever achieved. Still, none of this would matter if the film was made poorly.

Molester’s Train: Nasty Behavior is without a doubt Satô’s most polished film, not just story wise but technically as well. Mixing wide shots with claustrophobic zooms on character’s faces, Satô bends the world to his will. The viewer is put through the ringer with this film, with Satô masterfully putting together shots that help mirror the feelings of the characters. When characters are sad or feel lost, we feel the same. Facial zooms and frenetic editing accompany scenes of anxiety amongst the characters. The film never truly feels safe. While the action and acting is dramatic, it never once feels unrealistic. By far Satô’s most grounded movie, Nasty Behavior feels like a real story that is being told to the viewer. The acting in this is stellar as well, with the performances from our leads (portrayed by Yumika Hayashi and Kôichi Imaizumi respectively) are fleshed out and they feel like real people. Neither good nor bad, the characters feel like people who are just trying to get by and are complicated personalities. There are many layers to Nasty Behavior, and this would not have been possible without the quality of the performances here.

Molester’s Train: Nasty Behavior isn’t just the best film in the Molester’s Train series, but the best in acclaimed director Hisayasu Satô’s filmography and is one of the greatest pinku films of all time. If you can get your hands on this one, do it. Beautiful, depressing, haunting, and essential.

AKA: Chikan densha: Iyarashii kôi, Birthday, Tanjobi,

Molester’s Train: Dirty Behavior, 痴漢電車 いやらしい行為

Directed by: Hisayasu Satô

Written by: Kyôko Godai

Produced by: Daisuke Asakura

Cinematography by: Masashi Inayoshi

Editing by: Shôji Sakai

Cast: Yumika Hayashi, Kôichi Imaizumi, Kiyomi Itô, Yuri Ishihara, Hiroyuki Kawasaki, Shin’ichirô Kaneko, Yoima Yamishirô, Ichizô Kobayashi

Year: 1993

Country: Japan

Language: Japanese (English Subtitles)

Colour: Colour

Runtime: 54min

Studio: Kokuei Company

Distributor: Shintoho Company