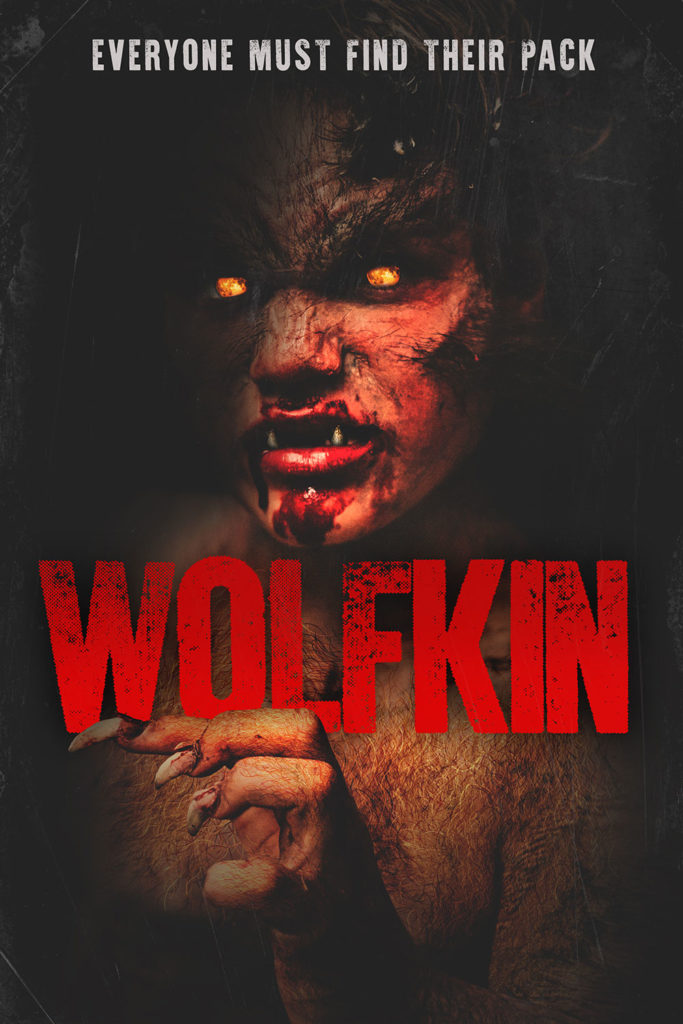

Wolfkin Review: A Captivating Exploration of Tradition and Transformation in European Werewolf Lore!

A little-known fact of 16th Century Europe — during the time of the witch trials in France, Latvia/Estonia, and the Netherlands there were also documented real life werewolf trials. Admittedly they were mostly medieval serial killers. Mostly. Other European legends of werewolves resided in Germany with tales of warrior clans dressed in wolf’s skin and even in certain cases fighting with wolves at their side in battle, or so the legends of the man-wolf go.

With that folkish DNA in mind, Wolfkin (a.k.a. Kommunioun in European film markets) is a Luxembourgian/French/Belgium production; directed by Jacques Molitor, in what might be his breakthrough film. Indeed, Wolfkin is elegantly shot and paced with true mastery and restraint, as does befit the subject matter of extreme, old-world self-control as a remedy for the modern, uncontrolled animalistic urges; a relevant theme for our times if ever there was one.

Wolfkin is an intimate familial lore about a single mother, Elaine, played with gritty modern realism by Louise Manteau (Black Spot), whose son, Martin, inexplicably bites other children in acts of unprovoked aggression. Martin is played convincingly and with nuance by young actor, Victor Dieu. Soon officials threaten to take him away her son if she cannot get him under control. The last shoe drops at Martin’s own birthday party where he bites another random victim.

Running out of options and sensing her boyfriend cannot really help her despite his best efforts, Elaine swallows her pride and visits Martin’s father’s parents as a last resort. Here the fable aspect of the story widens to include a welcoming set of stately, mentoring grandparents, played warmly and engrossingly by Marja-Leena Junker (Shadow of the Vampire, Skin Walker) & Jules Werner (The Merchant of Venice, Hysteria). This transition from Elaine’s claustrophobic single parenthood existence to the resplendent grand manner of the grandparents is palpable if not outright fantastic.

Despite 10-years of Martin’s Grandparents not even knowing he existed, upon first sight they fully accept him as a family member and are knowingly willing to help him ‘at this important time in his life.’ Subtle hints abound that his Grandparents are skilled at subduing animal urges, and in fact had to do the same thing for Martin’s Father, they confess. We also soon learn they haven’t spoken to Martin’s Father since he ‘ran away.’

Martin also has a new Uncle who lives at the Estate. He’s an entitled, ultra-aggressive, faux-aristocrat. Uncle insults Elaine as an unlikely and unwanted relative, but when the Grandparents accept Martin based on a birthmark and similarity of look to his father, he storms off in a furious huff. It is implied here Martin’s existence interferes with the last of a special bloodline and his own offspring’s potential succession to the estate. Uncle is pissed off but confident his pregnant wife will be the latest and greatest the family has to offer. Elaine tosses the uncle’s wife a smoke and shares some vodka, but the uncle steps in and mansplains why she can ruin her body after his baby is born healthily. Who’s the real monster, right?

Other old European traditions begin to seep into Elaine’s growing discomfort with the new fam, including attending church, Martin going to communion, and worse of all saying grace at a dinner where men and women eat different meals. Men eat meat pies. Women have soup. Elaine laughs at the tradition, causing Uncle’s pregnant wife to laugh a bit as well at the antiquated gender assigned menus. But the patriarch of the family, Grandpapa, settles them down with the help from Uncle, causing a violent stand-off with Martin getting involved as well.

With all this doubt about tradition at play, Elaine discovers Grandmamma is willing to lock Martin in a cage with barking dogs to tame him, and eventually willing to straight jacket and muzzle him like a rabid dog. Elaine correctly leaves, only for Martin to fully ‘wolf out’ as soon as they return to her teeny apartment, as the grandparents dance, knowing their tradition was the right course of action all along.

Eventually Elaine learns to trust the grandparent’s instincts until she learns murder is required to sustain this family unit. The ties that bind, indeed.

During this troubling time Elaine also has an overarching subplot, starting with an enticing opening sex scene where she dreams of an avatar self, fantasizing about (or recalling?) terrific sex with a mysterious, handsome man. Was it Martin’s father or was it a wolf? Later we suspect perhaps the opening sex scene isn’t a dream representation of Elaine but perhaps a cursed relative of century’s bygone, doomed to repeat the cycle, generation upon generation, in judgment for having a child out of wedlock. This memory/fantasy of hers is obscured at first in fable, then later as a sexual fantasy. Then finally by the truth of what occurred, revealing why she is really having all these furry feelings.

Wolfkin Downers:

Just the usual downer I find with European movies in general which is the prosaic, subdued, literal-mindedness and stoic, apollonian certainty with which they present everything; stone-baked in a haze of nihilistic post-WW2 glom. I kid our friends across the pond, of course. It’s rather provincial of me. It’s my personal hang-up and I am clearly being the downer here. Not Wolfkin in the slightest. Let’s move on.

Wolfkin Uppers:

I like the New World versus Old World dynamic. It’s a battle between the single woman and the traditional extended family (werewolves aside). The worldviews being contrasted here are a good match for each other in terms of stubbornness and self-importance. The freedom to be single and have children and the freedom to deny unhealthy relationships from continuing is a splendid right for everyone to have. However, the inability to control the little monsters they become without old-school discipline and the results it garnered in the past is also worth reflecting on. The downside is that children suffer the fallout of this untraditional family unit without the extended family support. It used to ‘take a village.’ I’m not sure what they say now? It takes a Tiktok trend? I’ll just leave this here before my uppers wear off.

The Direction of Wolfkin is also top-notch in every respect. I really felt like I was in the hands of a great director from the first frame till the last. Nothing took me out of the story. Nothing shook my confidence. I loved following Martin’s resurgence from troubled youth, to embracing structure and tradition. The acting was also superb from every cast member. I was convinced and enjoyed every minute of this film.

Overall, Wolfkin is clearly a recommendable film. It does great service to the werewolf subgenre and belongs up there with other Franco-centric werewolf films like Brotherhood of the Wolf (2001).

AKA: Kommunioun

Directed by: Jacques Molitor

Written by: Jacques Molitor, Régine Abadia, Magali Negroni

Produced by: Gilles Chanial, Olivier Dubois

Cinematography by: Amandine Klee

Editing by: Damien Keyeux

Music by: Daniel Offermann

Special Effects by: Quentin Bauwens, Nathan Beeckman, Sefian Benssalem, Pascal Berger, Jean Raymond Brassinne

Cast: Louise Manteau, Victor Dieu, Marja-Leena Junker, Jules Werner, Marco Lorenzini, Myriam Muller

Year: 2022

Country: Luxembourg, Belgium

Language: Luxembourgish, French (English Subtitles)

Colour: Colour

Runtime: 1h 30min

Studio: Les Films Fauves, Novak Production

Distributor: Uncork’d Entertainment